How Effective are Climate Finance Policies?

By Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Kelly Sims Gallagher, Fang Zhang

On February 3rd, a proposal to establish a National Green Bank was floated in both chambers of the U.S. Congress. The proposal calls for $100 billion Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator to help unlock credit and direct financing towards technologies that need to be commercialized. This proposal also follows closely on the heels of the recently released National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine report on deep decarbonization (co-authored by Kelly Sims Gallagher) which calls for a green bank at the federal level that can help capitalize local level green banks. It comes amidst reports that governments, corporations and other entities last year raised over $490 billion in green bonds and social impact vehicles.

The growing interest in foregrounding climate change in U.S. finance is also on the agenda of the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission and the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank. The U.S. Federal Reserve has signaled its intent to include study of climate-related risks in its oversight of U.S. banks as well as the wider financial system including stress testing the banking systems vulnerability to climate related losses. In addition to the new, more focused Federal Reserve oversight, the SEC has appointed its first climate advisor. Many U.S. companies report on climate risk in some form or fashion based on a ten-year old guidance statement on the topic which is now out of date. But often the information disclosed by companies is overly generalized and does not cover specific company data that is material for making investment decisions. Our research shows that greater engagement by the SEC is needed. It is now likely to be forthcoming.

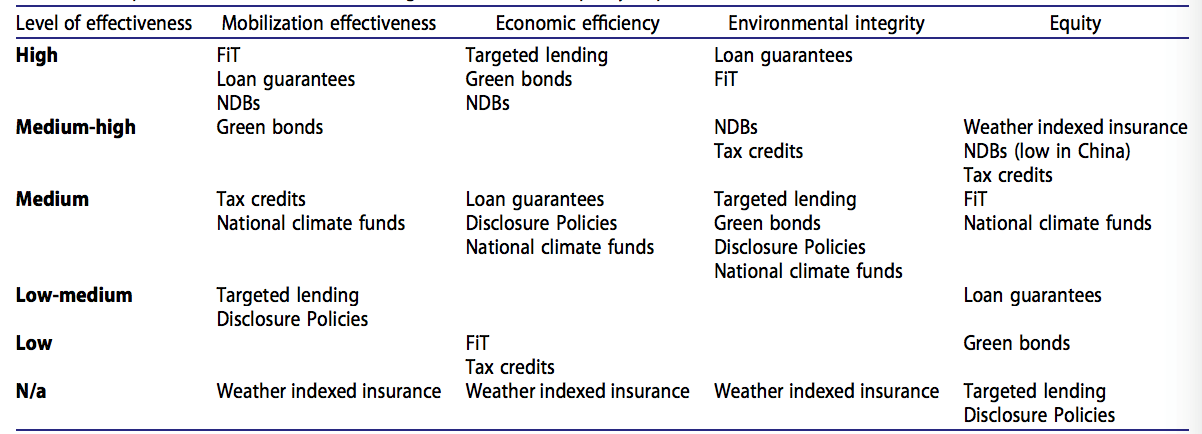

As policymaking gets a new, vigorous push in the United States, it is worth looking back to examine how successful previous policies have really been in mobilizing climate finance. In a recently published paper, we gather insights from the numerous policy experiments taking place around the world. We investigate nine types of climate finance policies: target lending, green bond policy, loan guarantee programs, weather-indexed insurance, feed-in tariffs, tax credits, national development banks, disclosure policies, and national climate funds. To make the comparison systematic, we identify a set of four criteria that we use to score the policies. These criteria are: mobilization effectiveness, economic efficiency, environmental integrity, and equity.

Our comparisons illustrate how different instruments can have varying levels of reach and economic costs. We find that feed-in tariffs, tax credits, loan guarantees, and national development banks all succeeded in mobilizing private finance (as shown in Table 1) but that the relative costs of each approach varied significantly. For example, feed-in tariffs, though highly effective in mobilizing finance (mobilization effectiveness), impose significant costs to government, thereby scoring this mechanism lower on economic efficiency than other approaches such as loan guarantees and green bonds. Some national climate funds were structured with dedicated windows that focus exclusively on small grants or community based climate programming (high on the equity score), but they have not been able to mobilize climate finance in a consistent manner (low on the mobilization effectiveness metric). Similarly, tax credits score relatively low on social equity because they are based on tax liabilities which thereby often benefit wealthier entities or individuals.

Table 1 Comprehensive assessment and rating of climate finance policies in practice

Policies such as green bonds have taken off but their environmental effectiveness is not clear. Given the wide variety of definitional standards surrounding green bonds, it is difficult to compare the actual environmental impacts of green bonds. Likewise, climate risk disclosures made by companies can lead to changes in investment decisions but research shows that companies that make the most sustainability pronouncements outperform, suggesting that consistent disclosure rules would be helpful. In both cases, tighter definitions, improved transparency and consistent reporting is needed to improve environmental performance.

One of the key messages of this paper is that no single policy is perfect. Policies have different strengths and weaknesses. Generally speaking, our research suggests that climate finance policies tend to emphasize the need to mobilize finance more than other factors given capital scarcity, whereas measurable environmental performance and social impacts are often neglected. Our study shows that policy makers must factor in a wider set of standards and metrics to ensure policy instruments strike a balance between financial mobilization effectiveness, economic efficiency, environment integrity, and equity.

At the heart of climate finance efforts by the U.S. and other governments should be the lesson that the effectiveness of any of the many financial tools that can be utilized is that their effectiveness is conditional on sound policy design. We examine how the nine climate finance policies score on five key design features: stability, simplicity, transparency, consistency and coordination, and adaptability. For example, as loan guarantee programs are sensitive to budget negotiations, they lack consistency in implementation because government priorities may change but they are effective in mobilizing finance. Policy makers need to be aware of such trade-offs.

We also find that financial policies and instruments can be more effective when they are embedded in larger, supportive frameworks. No single policy can achieve the heavy lifting alone – policy mixes are required. Our research shows that when policies are nested in larger, supportive frameworks they are more likely to have positive impact. For example, Germany’s feed-in tariff program has been successful in deploying renewables and achieving cost reductions. KfW’s low cost financing and refinancing mechanisms for regional and local banks were instrumental ensuring participation in the feed-in tariffs program.

Importantly, it is also striking that there is a general lack of transparency and data around the fairness of climate finance policies. This problem must be addressed going forward. Although green bond markets are soaring, they are not currently designed to address equity concerns as they tilt towards large corporations rather than small and medium firms. Government loan guarantee programs can have the same deficit, if they do not target smaller entities in the way the U.S. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program does as well as the German KfW work with local and municipal governments on renewable energy.

National experience with different climate finance policies has been mixed, in part due to the varying quality of related policy design. Moreover, some of policy instruments (e.g. weather indexed insurance, climate bonds) are relatively new and remain understudied. The effectiveness of policies has also changed with shifts in technology trends and market conditions. As the costs of renewable energy technologies have fallen, governments have moved away from costly feed-in tariffs and are shifting to reverse auctions where developers compete to submit the lowest priced bids for government contracts.

Public domestic climate finance expenditure is easier to track than private finance. Without more data on private finance, it is challenging to know the impact of policies in mobilizing private finance. Apart from understanding the ‘leverage’ effect of public policies, more private finance data is needed to allow better analysis whether public climate finance is unintentionally crowding out private finance and whether the level of concessionality of public finance is appropriate or not. That’s important because where it can be demonstrated that the need for subsidies and concessional finance is fading due to technology breakthroughs, climate finance could be freed up for to other purposes.

So, what does this mean for the United States? Our research suggests several immediate policy implications for the Biden administration as it gears up to accelerate action on climate change.

Green Banks.

Several state-level green banks already exist in the United States. A federal green bank that builds on local and state-level institutions would help to unlock the power of the federal government in accelerating spending. Our research on national development banks shows that they play an important coordinating function. Having an institution at the federal level could help ensure broader geographic distribution of green finance across the United States, ensuring more regional equity. A green bank can also play an important counter-cyclical stabilizing role by providing finance during economic downturns.

Definitions.

Green bonds do not have a globally agreed definition. Various taxonomies have started to emerge such as the EU taxonomy. Similarly, disclosure standards are numerous and complex, not to mention only voluntary. In both of these instances, the Biden administration needs to work with the private sector and interested governments to harmonize definitions and enforce uniform and transparent disclosure.

Policy mixes.

The administration should adopt a suite of complementary policies to help unlock climate finance and pay attention to how to prevent overlapping policies from creating negative or conflicting consequences.

Rishikesh Ram Bhandary is a postdoctoral scholar at The Fletcher School, Tufts University.

Kelly Sims Gallagher is the Academic Dean and a Professor of Energy and Environmental Policy at The Fletcher School, Tufts University.

Fang Zhang is an Assistant Professor at Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management.