Trends in US Public Investment in Low-Carbon RD&D

By Kelly Sims Gallagher and Laura Diaz Anadon

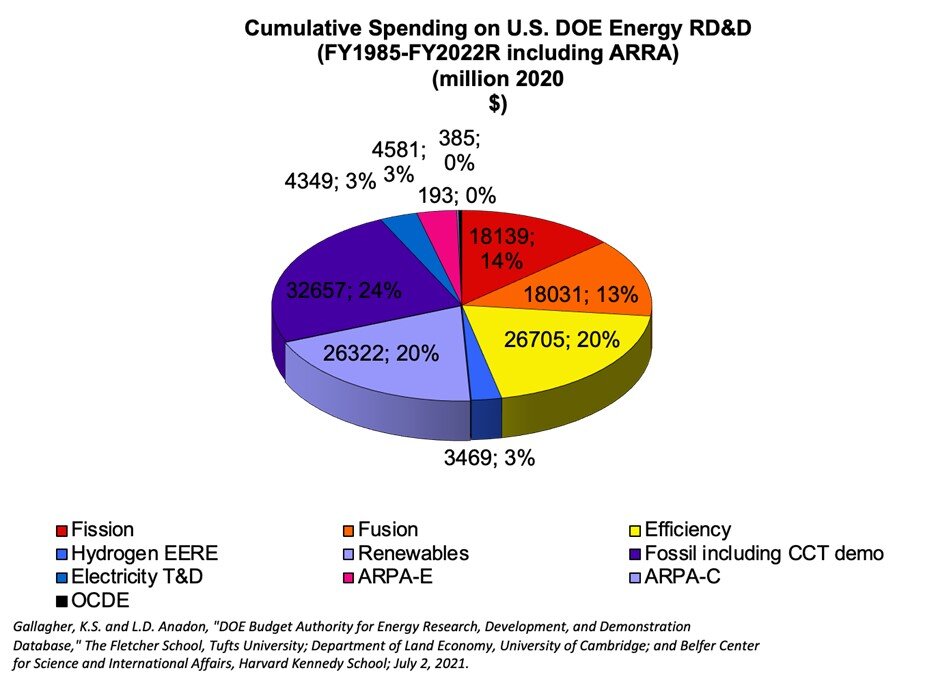

President Joe Biden’s first budget release provides an initial glimpse of the Biden Administration’s priorities for technological innovation in low-carbon energy. Importantly, the fiscal year (FY) 2022 request would sharply increase US government investments in research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) in energy efficiency and renewables. We have tracked US government investments in energy RD&D for many years, and the proposed Biden allocations are part of a longer upward trend (See Figure below). Our newly updated U.S. R&D database is available open-access at Tufts University and Cambridge University. For the coming year, smaller increases are proposed for nuclear fission, carbon capture and storage for fossil energy, and ARPA-E. The Biden Administration proposes to create two new innovation institutions: an ARPA-C and an Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). Overall, the Biden Administration proposes to increase clean energy RD&D by 37% from FY21 levels.

One of the biggest surprises from the Trump era was that government energy RD&D investments did not decline, despite historic proposed cuts to clean energy RD&D by the Trump Administration. Actually, in constant 2000 dollars, overall public energy RD&D rose by 16% between FY18-FY21.

Congress has consistently demonstrated support for an energy RD&D portfolio that covers a wide swath of energy technology categories rather than a focused effort. In addition, FY20 and FY21 appropriations were the highest since 1982 (except for 2009 when the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act was passed) and if the FY22 request is honored, the levels would be higher than any years except 1978-1981 when the United States was reacting to the oil crises of the 1970s. Cumulatively since FY1985, the United States has devoted similar proportions of its budget to different high-level technology categories, with 20% spent on renewables, 20% on efficiency, 24% on fossil fuels, and 27% on nuclear (fission and fusion).

The historic cumulative portfolio of relatively equal weighting among types of energy is likely to be inappropriate for today, however, given the climate crisis and economic recovery required following the pandemic. The FY22 request for energy efficient research and development is roughly equally divided across transportation, industry, and buildings. Within renewables, all categories grow compared to the FY21 budget, including storage. Nuclear fission increases in the FY22 request and is the third-largest category, which is interesting given that the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission has only approved four new reactors since 1973 (and construction on two of them was halted in 2017). The Biden administration looks set to continue the Trump administration’s interest on small modular reactors (SMRs). At least half of the fossil fuel budget request would be devoted to carbon capture and storage, although there may be additional CCS within in the coal R&D category (additional distinctions are not possible given how the Statistical Tables submitted with the Budget Request are structured). For the first time, the Biden Administration proposes new budget requests for mineral sustainability and carbon removal technology. It also plans to zero out research funding for petroleum and unconventional fossil energy. Signaling an ongoing commitment to natural gas, the new budget would more than double the investments in gas-related RD&D. Electricity transmission and distribution would essentially stay stable, with a focus on reliability, smart grid, and cyber security. ARPA-E funding slightly increases and a second ARPA-like agency is proposed: ARPA-C. We remain keen to learn more details about this and the rationale for a separate climate solutions-related agency.

Perhaps most innovative aspect of the Biden Administration’s budget request is a new Office of Clean Energy Demonstration. The United States has lagged both China and Europe in demonstrating advanced energy technologies. Without pre-commercial demonstration, many technologies languish in the dreaded Valley of Death so this new office could play an important role depending on how it is staffed, structured, and resourced.

Finally, what is missing? As always, there is a very strong “technology push” bias in the budget. DOE considers itself to be a science agency. The reality, however, is that technologies must be adopted and used by people and firms and should reflect the wider values and goals of society as reflected through the elections process. This year, it is clearer how DOE must expand its work in technology deployment to reflect a wider set of metrics for innovation as well as broader performance standards by industry. There are many questions that the government urgently needs to answer. What are the barriers to adoption of technologies that can be used to meet net zero goals across sectors? Why do people sometimes decide to not buy advanced or cleaner technologies even when they are as cheap as the conventional option? To what extent are different policies working to create markets for advanced technologies? How much tax-payer funded research results in new jobs and new economic growth? How do energy innovation investments affect the nation across a range of goals, including biodiversity, health, and social justice? Are they distributed equally in terms of geography, gender, race? Do the benefits accrue to certain segments of society and not others? In the FY23 budget, we hope to see some new programs that will allow researchers to pose and answer these questions. ∎

Kelly Sims Gallagher is the Academic Dean and a Professor of Energy and Environmental Policy at The Fletcher School, Tufts University. She is also co-director of the Center for International Environment and Resource Policy and the director of the Climate Policy Lab.

Laura Diaz Anadon is a Professor of Climate Change Policy at the University of Cambridge.