The Afterlife of Clothing: Understanding Haiti’s Pèpè

This blog is a part of our 2025-2026 Climate and Cultural Heritage Series made possible by the Fletcher Center for International Environment and Resource Policy and the Fletcher Office for Inclusive Excellence.

By Nadjee Jocelyn

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about clothes, not in the fun, “let me plan my outfit for class” way, but in a heavier way. More like: what does it actually mean to get dressed on a dying planet?

Because once you ask that, you start noticing things you’ve ignored, the pace of consumption, the piles of clothing in thrift stores, and the way the fashion industry moves faster than our ability to make sense of it. And for me, as someone Haitian, that question naturally leads to pèpè, the secondhand clothing that’s become part of the fabric of everyday life in Haiti.

I didn’t need to walk the markets in Haiti to understand the presence of pèpè. The word alone tells a whole story. For those unfamiliar, pèpè is the Kreyòl term for the entire secondhand clothing trade, the imported bales of used garments from the U.S. and Europe, and the resale networks that break them open, sort them, and move them through Haitian markets. These clothes end up shaping how so many Haitians get dressed. And when you zoom out, you realize pèpè isn’t just about what people wear. It exposes the structure behind who produces, who consumes, and who absorbs the excess.

Pèpè Isn’t Charity, It’s a System

In the U.S., donating clothes feels like the “responsible” thing to do. People toss things in a bin and walk away feeling lighter. But behind that simple act is a whole global chain: sorting warehouses, exporters, bulk buyers, and shipping containers that eventually land in places like Haiti. And by the time those clothes arrive, they’re not “donations.” They’re inventory.

The low prices might seem like they help people, and in some ways they do, but those same cheap imports pushed Haiti’s local textile and tailoring culture into the background. With pèpè flooding the markets, it became impossible for many local makers to compete. So Haiti didn’t just choose secondhand clothing. It was flooded with it.

And while the low prices of pèpè can make clothing more accessible for Haitian families, there is a deeper cost that often goes unspoken. Large-scale imports of secondhand clothing into Haiti began as early as the 1960s, during U.S. trade liberalization efforts under the Kennedy administration, and expanded steadily over time. As these imports increased, and especially with the rise of fast fashion, pèpè flooded Haitian markets, making it increasingly difficult for local tailors, seamstresses, and small garment businesses to compete. Haiti didn’t gradually shift toward secondhand clothing; it was pushed there by global economic flows that favored cheap imports over local craftsmanship (Dazed, 2024).

This is where the sustainability narrative becomes complicated. Secondhand clothing is often framed as environmentally friendly because it extends the life of a garment, and in theory, reuse is better than disposal. But in practice, not every piece of pèpè gets worn, and not every piece is usable. Alongside wearable garments, shipments frequently include damaged or low-quality clothing that cannot be resold. In Haiti, where waste management systems are already under strain, these unsellable textiles often become waste, piling up in canals, being burned in open air, or ending up in informal dumpsites. What is presented as reuse or recycling can quickly turn into an environmental issue, adding another layer to the pressures Haiti already faces (Dazed, 2024).

Because the truth is, not every piece of pèpè gets worn, and not every piece is usable. The lowest-quality items, the stretched-out Shein shirts, the stained North Face sweaters, the pieces that never should’ve been donated in the first place, end up as waste. And in Haiti, where waste management systems are already strained, that becomes an environmental issue as much as an economic one. Discarded clothing piles up in canals, gets burned, or sits in open dumps, adding another layer to the environmental stress the country already faces.

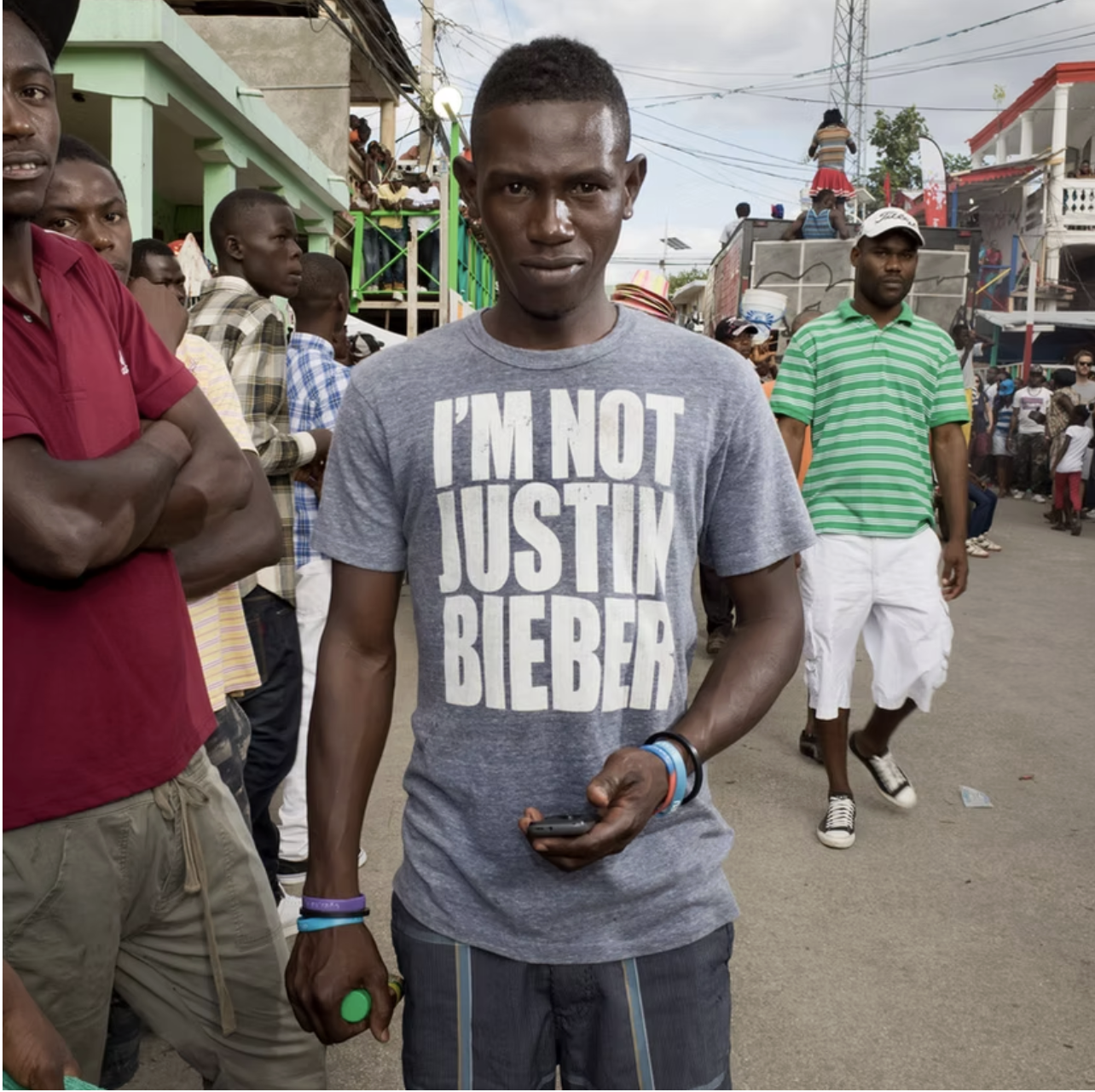

(Photos by Paolo Woods)

And yet, even within all this, Haitians do what they’ve always done, make the best of what arrives. People take the most random T-shirts and style them like they were intentionally chosen. There’s creativity, pride, and a sense of identity that transforms discarded pieces into something new. It’s one of the things I love most about Haitian people: the ability to create dignity and expression out of anything. But that shouldn’t be mistaken for consent. It shouldn’t be taken as a sign that the system is harmless.

When I think about pèpè, I don’t see charity. I see the underbelly of fast fashion: who gets to discard, who has to receive, and who holds the environmental consequences. Haiti deserves more than to be the endpoint of the fashion industry’s excess. And while pèpè is undeniably part of the economy and everyday life, it shouldn’t be the only option for Haitians and other people whose countries are forced to take in excesses of secondhand clothes.

Imagining something better means thinking beyond donated clothes and looking toward rebuilding Haiti’s own textile identity, supporting tailors, regulating the quality of imports, investing in upcycling and recycling systems, and creating the kind of infrastructure that allows Haiti to shape its own fashion future rather than inheriting everyone else’s leftovers.

So when I ask myself what it means to get dressed on a dying planet, the answer isn’t just about individual choices. It’s about understanding the global systems behind those choices, where clothes go, who carries the weight of our consumption habits, and how countries like Haiti are pulled into the climate story without ever being centered in it.

Getting dressed is simple. But what happens after we’re done wearing something is anything but. And if we’re going to talk about sustainability, we can’t just celebrate reuse without acknowledging where that reuse actually lands. Some places get thrift stores; others get shipping containers. Some get the “trend”; others get the aftermath.

Nadjee Jocelyn is a Master of International Business Student at the Fletcher School.